By Angela Dansby and Dale Thorenson

By Angela Dansby and Dale Thorenson

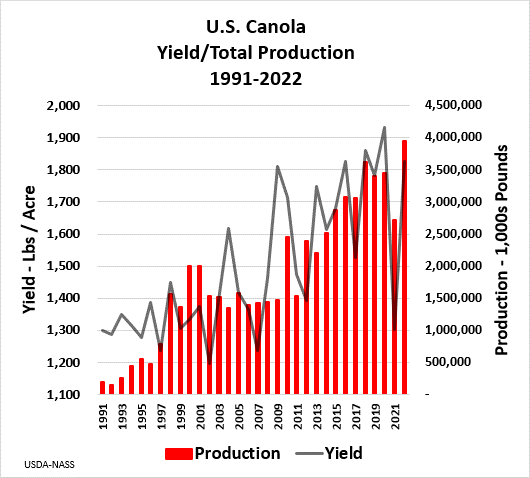

U.S. canola had record production this year, up a whopping 45 percent from 2021, according to the Oct. 12 crop report from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS). Nearly 2.2 million acres were harvested with an average yield of 1,826 pounds per acre, resulting in 3.95 billion pounds of canola.

Looking back 30 years at NASS records, U.S. canola production has grown in spite of ebbs and flows, increasing more than 95 percent from 191 million pounds to nearly 4 billion. Yield has been erratic with several big dips (2002, 2007, 2012, 2017 and 2021) influenced by Mother Nature, however, production well outpaced yields during those years. More importantly, canola genetic traits have continued to improve, largely driving the 500-pound/acre increase since 1991, when yield was only 1,300 pounds per acre.

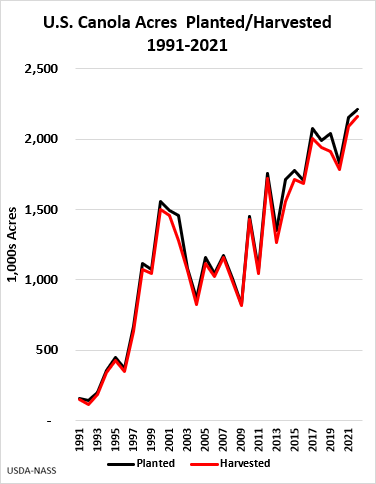

Planted and harvested U.S. canola acres have grown dramatically from around 150,000 in 1991 to well over 2 million in recent years. Planted and harvested acres were generally well aligned until the past eight years, when climate change began driving Mother Nature crazy, decreasing harvests more than usual. Due to the climate crisis, it is likely such noticeable gaps between planted and harvested acres will continue.

Planted and harvested U.S. canola acres have grown dramatically from around 150,000 in 1991 to well over 2 million in recent years. Planted and harvested acres were generally well aligned until the past eight years, when climate change began driving Mother Nature crazy, decreasing harvests more than usual. Due to the climate crisis, it is likely such noticeable gaps between planted and harvested acres will continue.

State Stats

In 2022, North Dakota led U.S. canola production as usual with nearly 3.42 billion pounds, followed by Washington (231.4 million), Montana (159.6 million), Minnesota (127.84 million), Oklahoma (5.6 million) and Kansas (3.78 million).

North Dakota has the longest history of canola production and since 1998, it has essentially doubled production. Since 2005 and 2001, respectively, Montana and Washington have had an upward production trend as well. Montana has gone from about 9.6 million pounds (2007) at its lowest to its highest this year at nearly 160 million. Washington has increased from about 19.4 million pounds in 2011 to its record of more than 231 million in 2022.

Other canola-producing states, namely Idaho and Oklahoma, have experienced volatility; Oregon remains relatively low and flat due to planting restrictions; and Minnesota and Kansas have generally produced less than when record-keeping began. Oklahoma production peaked in 2013 at nearly 209 million pounds, then dropped dramatically to its lowest ever this year under 6 million.

The NASS last recorded production in Idaho in 2018 at 88.2 million pounds, but levels fluctuated between 2009 at 24.7 million to “not available” in 2019-20. Similarly, Oregon fell off the grid after 2018, when it only produced nearly 7.7 million pounds of canola. Prior to that back to 2009, Oregon production ranged from as low as 3.2 million pounds (2015) to as high as 19.4 million (2013). While the NASS no longer surveys Idaho and Oregon for canola planted acreage and production, the Farm Service Agency (FSA) requires farmers to report planted acreage each year. FSA data indicates canola acreage has increased substantially in Idaho and Oregon in the last four years with nearly 70,000 and 7,000 acres, respectively.

In Minnesota, the NASS recorded a peak of 290 million pounds in 1998, which dropped to a low of nearly 21.3 million in 2009. It has been slowly making a comeback, but this year’s production was still less than half of what Minnesota produced 24 years ago. Kansas peaked in 2017 with 62 million pounds of production, which has since taken a nosedive to less than 4 million this year.

Thankfully, the volume of North Dakota and growth trend in Montana and Washington are likely to continue to drive up U.S. canola production for the foreseeable future. Of course, Mother Nature, and therefore farmers, will also continue to be challenged by climate change. But at least the resiliency of canola will be consistent.

Angela Dansby is director of communication and Dale Thorenson is assistant director of the U.S. Canola Association.